It is high time to get to work, catching up on movies. The survival of cinema depends upon it! Cinephilia will save the movies if anything will, but it will require a sizable sacrifice, punishing abuse of the eyes and ears of all those willing to chip in, tirelessly consuming all manner of films, old and new. And as it happens, I have invented a quick and easy method for doing so. I want to help you help cinema.

But first, a crucial question: Why are movies good? Of course, not all movies are good, but in general, movies are good for you. Movies are good for you because they fulfill four essential needs:

One is the need for mystery, preferably with strong desire and suspense, and without final solutions (this is what links Brakhage, Hitchcock, and Lynch);

Two is the need to encounter virtual actuality: the unmistakable but fleeting recognition of things as simultaneously past and present, here and not here (a.k.a. realism; Barthes called it punctum), which happens periodically, but not constantly, and includes that feeling of shock or surprise of a real encounter crossed with unreality of some kind (see Harryhausen, Sternberg’s Dietrich, Buster Keaton, Jackie Chan, Tarzan’s yell);

Three is the need for tricks, jolts, and surprises—cinema’s connection to magic and “show me” attractions of all kinds;

Four is the need for time, immersion in cinematic time, which is not the same as time outside of movies—every bit as actual, but more malleable, less linear (as Andrei Tarkovsy believed, time is matter, cinema’s raw material, just like marble is a sculptor’s raw material; as Dr. Who defines it, time is “a big ball of wibbly wobbly, timey wimey…stuff”).

In most movies, these four services are mixed together in varying amounts and intensities. Some are mostly mystery, others more punctum. Some are mostly for the tricks, and some are more temporal playground.

Bad movies are those which give up too many answers in the process of delivering the mystery; those which try for realism but lack punctum; those with no surprises; those which suppress time rather than sculpting it; and those which fail to successfully deliver a concoction of the four ingredients in such a way as to lodge themselves (or bits of themselves) in your mind afterwards, at least for a little while.

Motion pictures existed long before cinema: in cave paintings, Chinese scroll paintings, and Renaissance frescoes, and later on in panoramas, zoetropes, phenakistoscopes, and photographic motion studies. But that is the subject of some other list, not this one. This list starts at the beginning of the art/technology called cinematography, and zips forward to about 1939, focused on films that mine one or more of the four elements listed above.

The method is simple: Find all of the movies on this list and, for 7 days straight, spend about nine hours per day watching them, in whatever format you can find (online, DVD, or even VHS)—all the while realizing that, unless you luck out and catch a screening of one of them on film film, you are watching a shadow of the real thing. As long as you keep that in mind, these movies will nourish you. All you have to sacrifice is one week. You can do it!

Note: If there are any titles on this list which you have seen before, not to worry. You can stand to see them again.

Annabelle Serpentine Dance (W.K.L. Dickson & William Heise, 1895) [1 minute]

What cinematography was invented to do: capture a nonstop event without having to stop it.

The Arrival of a Train (Lumiére Bros. actuality, 1896) [1 minute]

Look out!

Indochina: Namo Village, Panorama Taken from a Rickshaw (Lumiére Bros. actuality, c. 1897) [1 minute]

Not your typical Lumiére film (way more fun).

Egypt: The Pyramids (Lumiére Bros. actuality, c. 1897) [1 minute]

A lesson in framing and depth, with camels.

Mexico: Bathing the Horses (Lumiére Bros. actuality, c. 1897) [1 minute]

In the process of revealing that horses are afraid of ducks, this short actualité demonstrates actual actuality quite poetically, as the camera captures actual events unfolding differently from the plan.

Four Heads Are Better than One (Georges Méliès, 1898) [1 minute]

Méliès was a magician and a showoff—i.e., ideally suited to make movies.

A One-Man Band (Georges Méliès, 1900) [2 minutes]

More Méliès (literally).

How It Feels to Be Run Over (Cecil B. Hepworth, 1901) [1 minute]

Best one-shot movie ever?

The Man with the Rubber Head (Georges Méliès, 1901) [3 minutes]

Best exploding head movie ever?

Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (Edwin S. Porter, 1906) [7 minutes]

You know what happens when you gorge yourself on Welsh rarebit and then go to bed, right? This is a live action adaptation of Winsor McCay’s eponymous comic strip (one of the specific strips adapted for the film can be seen here).

From Leadville to Aspen: A Hold-Up in the Rockies (F.J. Marion & Wallace McCutcheon, 1906) [8 minutes]

Cut to the chase! A typical early “view from a train” film transforms into a crime thriller movie.

The Irresistible Piano (Alice Guy-Blaché, 1907) [4 minutes]

All the inhabitants of an apartment building succumb to dance fever.

Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy (Stuart J. Blackton, 1909) [5 minutes]

No description necessary—just watch.

The Land Beyond the Sunset (1912) [14 minutes]

Street urchin is plucked from the city streets to be shown the country by charitable ladies of the “Fresh Air Fund,” and things get surreal. Stick with it for the surprise ending!

Falling Leaves (Alice Guy-Blaché, 1912) [12 minutes]

Guy-Blaché’s lyrical short about an upper class family facing a problem typically associated with the poor: consumption (a.k.a. tuberculosis). Although the film uses the tableau style (one shot per scene), Guy-Blaché makes great use of depth, allowing the actors to define the drama by their movement (and stillness) within the space.

How a Mosquito Operates (Winsor McCay, 1912) [6 minutes]

An early animation McCay based on his popular comic strip mentioned above. This film was used as part of McCay’s traveling vaudevillian show, wherein he projected the cartoon and interacted with it live on stage.

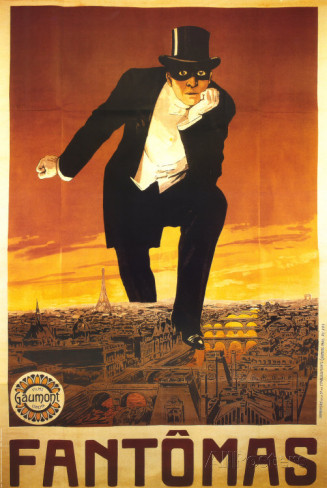

Fantômas (5 episodes) [337 minutes]

Les Vampires (10 episodes) [417 minutes]

Judex (12 episodes + epilogue) [300 minutes]

Regeneration (Raoul Walsh, 1915) [72 minutes]

Walsh was a D.W. Griffith protégé who continued to make great action movies in Hollywood into the 1930s. This film survived by the skin of its teeth and exists now only in severely damaged form, which only makes it tougher and more beautiful.

A Muddy Romance (Mack Sennett, 1913) [11 minutes]

When he heard that Echo Park Lake was going to be drained, Mack Sennett took the opportunity to make this film in which a wedding on a boat is thwarted when a jealous ex drains Echo Park Lake. A muddy mess featuring the Keystone cops in one of their earlier appearances.

A Dog’s Life (Charles Chaplin, 1918) [33 minutes]

Just right.

Young Mr. Jazz (Hal Roach, 1919) [10 minutes]

Harold Lloyd dances and fights!

The Play House (Buster Keaton, 1921) [18 minutes]

How many Buster Keatons does it take to put on a show (and wreck it)?

La Glace à trois faces [The three-sided mirror] (Jean Epstein, 1927) [45 minutes]

Mystery and romance, a twist ending, a killer bird… What more could you want?

La Coquille et le clergyman [The Seashell and the Clergyman] (Germaine Dulac, 1928) [28 minutes]

Don’t think, just take it in. An argument for cinema.

Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel & Salvador Dalí, 1929) [16 minutes]

Slicing up eyeballs! Dream logic meets the language of the movies.

L’Hippocampe [The Sea Horse] (Jean Painlevé & Geneviève Hamon, 1934) [15 minutes]

Instructional surrealism. Science meets cinema.

H2O (Ralph Steiner, 1929) [13 minutes]

A great film about water, documenting the effects of light on moving H2O. Cinema was invented for this. By the end of the film, it becomes as abstract and dazzling as a film can be.

Rose Hobart (Joseph Cornell, 1936) [19 minutes]

Found footage of silent star Rose Hobart, reassembled into a surreal jungle dream.

La Roue [The Wheel] (Abel Gance, 1923) [273 minutes]

It lasts a lifetime, but for good reason. Slow your heart rate and live in it.

Der letzte Mann [The Last Laugh] (F.W. Murnau, 1924) [90 minutes]

Murnau’s “unchained camera” captures the devastation and redemption of a proud luxury hotel doorman in a time when a devastated Germany was working on its own redemption.

Apropos de Nice (1930) [25 minutes]

Taris, roi l’eau (1931) [10 minutes]

Zero de Conduit (1933) [41 minutes]

L’Atalante (1934) [89 minutes]

Hallelujah (King Vidor, 1929) [109 minutes]

This is Vidor’s first sound film. Siting atop Hollywood’s A-list, he could have chosen any project he wanted. He chose this story of black sharecroppers in the Deep South, and he chose to shoot it on location with an all black cast. The studio was not pleased. He made the film anyway. It turned out sublime.

M (Fritz Lang, 1931) [99 minutes]

This is Lang’s first sound film and Peter Lorre’s first big movie role. Maybe the best movie about (a) the limits of vision, (b) the value of listening, (c) surfaces and (d) (psychological) depth. The whistled tune, in case you’re wondering, is Grieg’s “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” written for the part of a play (Peer Gynt) where the hero must face a bunch of trolls, gnomes, and goblins.

Tabu: A Story of the South Seas (F.W. Murnau & Robert Flaherty, 1931) [86 minutes]

For his final film (he would die in a car crash just before its premiere), Murnau teamed up with the blockbuster documentarian, Flaherty, for this silent/sound film about love, light, skin, money, sharks, and one big pearl.

The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933) [71 minutes]

Having adapted Frankenstein quite successfully (see below), James Whale tackles H.G Wells’ best novel, and casts the outstanding Claude Rains in the title role, for which he does not appear (except in voice) until the film’s final shot.

42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933) [89 minutes]

Dance and excess, Busby Berkeley style!

From Universal:

Frankenstein (1931) [70 minutes]

Bride of Frankenstein (1935) [75 minutes]

Son of Frankenstein (1939) [99 minutes]

From MGM:

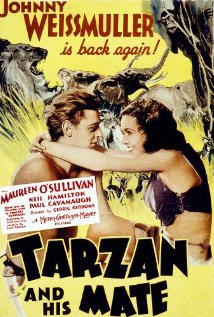

Tarzan the Ape Man (1932) [100 minutes]

Tarzan and His Mate (1934) [104 minutes]

Tarzan Escapes (1936) [89 minutes]

Tarzan Finds a Son! (1939) [87 minutes]

Tarzan’s New York Adventure (1942) [79 minutes]

From Warner Bros./First National:

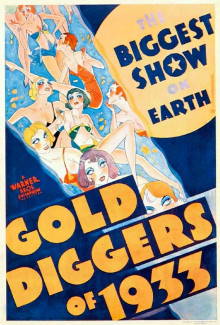

Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933) [97 minutes]

Gold Diggers of 1935 (1935) [95 minutes]

Gold Diggers of 1937 (1937) [101 minutes]

Gold Diggers in Paris (1938) [97 minutes]

The Crime of Monsieur Lange (Jean Renoir, 1936) [80 minutes]

Pépé le Moko (Julien Duvivier, 1937) [94 minutes]

Le Quai des brumes [Port of Shadows] (Marcel Carne, 1938) [91 minutes]

The Wizard of Oz (1939) [first 99 minutes]

...But only if you stop the movie before the end. DO NOT LET DOROTHY GO BACK TO KANSAS! Salman Rushdie is right: the movie’s ending, in which Dorothy opts to return to Kansas, strays away from the whole thrust of the fantasy, away from “the anarchic spirit of the film.” Stop watching right after the Lion suggests that Dorothy stay in Oz, with those who adore her, in the place where she has built a family and become a hero. Imagine that she says, “Yes, I think I will stay.” The end.

Okay, now you’re warmed up and ready to start the real work. In the next few “must-see” installments, we will delve deeper into the first 50 years of cinema while also skyrocketing forward in history, all the way past the year 2000!

Next list: MOVIES ABOUT MOVIES! Coming soon...